When you squeeze a sealed balloon on one end, the air doesn’t simply go away; rather, it just finds another part of the balloon to expand. In other words, the air must go somewhere. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) will create a similar dynamic with drug costs for Medicare payers and drug manufacturers. When the Medicare redesign is fully implemented in 2025, payers will incur 4 times higher liabilities for catastrophic coverage compared to the 2023 defined standard benefit and will lose a 70% manufacturer contribution for drugs currently filled during the coverage gap phase. Moreover, beginning in 2024 Medicare Part D plan premium growth will be capped at 6%. On the other hand, drug manufacturers, especially those of high-cost drugs, will have to pay considerably higher levels of contribution, as they will be required to pay 20% of drug costs in the catastrophic phase and 10% in the initial coverage phase. Keep in mind that a high-cost drug typically blows right through the current-day coverage gap. In the new design, they will have multiple fills in the catastrophic phase, in which they currently have no required contribution.

Returning to our balloon analogy, we see that the drug cost balloon is being squeezed at both ends, that of the payer and that of the manufacturer. With higher liabilities and added controls on premiums, payers will need to look for offsets elsewhere. Historically, these have come from higher rebate demand and utilization management controls. At the same time, drug manufacturers are also being squeezed by higher liabilities coupled with stronger rebate demands. However, their traditional approach of raising WAC (wholesale acquisition cost) prices is now further constrained by inflationary caps and AMP (average manufacturer price) cap implications in Medicaid. The question becomes, where does the money come from? Enter in the discussion of net cost and WAC vs. rebate.

Shortly after the IRA was released in August 2022, PRECISIONvalue conducted a small survey of payers (N=25) to gauge their reactions to its impacts. We found that approximately two-thirds of payers will continue to seek aggressive rebates to offset higher cost liabilities. Yet the same number of payers also indicated a stronger preference for low WAC drugs, including generics and biosimilars. From these results, we can infer that low net cost will ultimately win. It’s simply a matter of how we get there.

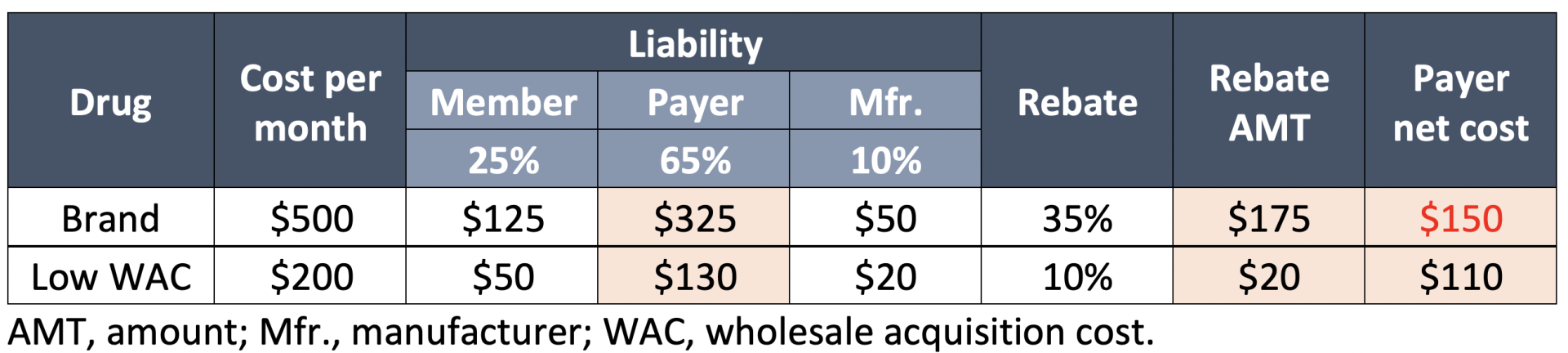

Consider the following example that occurs within the initial coverage phase, post IRA implementation in 2025. There are two brand drugs, one with a 60% lower WAC price.

In this example, the original brand drug is more expensive for the payer because, despite the higher rebate, it is not high enough to achieve a lower net cost. Additionally, the lower-price WAC drug is markedly less expensive for the member and will likely be preferred, even if the rebate is increased on the brand to bring down the net cost simply because it has a lower out-of-pocket cost.

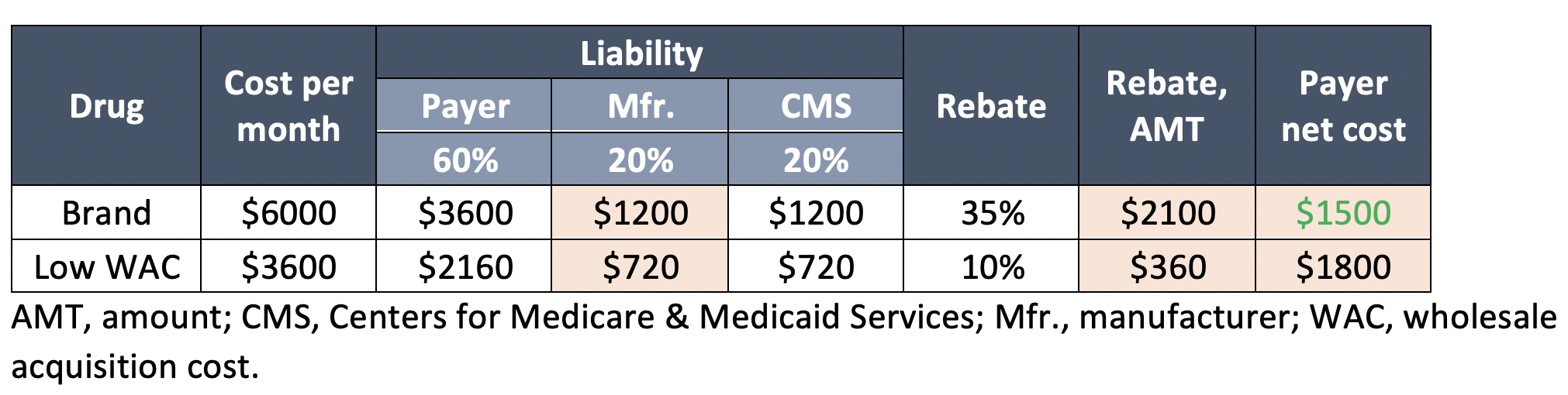

Now let’s look at an example of a specialty drug that competes against a lower WAC alternative, which costs 40% less. (This may simulate a biosimilar situation.) Also, remember that now we are comparing costs in the catastrophic phase (post IRA implementation), in which most specialty prescription fills occur and the member will not have any out-of-pocket costs.

Unlike the previous example, the higher WAC drug has a lower net cost to the payer. Much of this is attributed to the rebate offsets that result from negotiated rebates in addition to the required 20% contribution mandated by the government. And since there is no patient out-of-pocket cost in either situation, the low net cost product will have the upper hand in achieving preferred access.

Both scenarios involve a balancing act between rebate negotiation and pricing strategy of lower WAC alternatives. The latter approach poses some additional opportunities for manufacturers to consider. For example, launching new formulations or new National Drug Codes ( of existing brands at lower WAC prices helps to avoid AMP cap penalties in Medicaid. They also provide options to play the net cost game from both ends of the spectrum. However, there is no one-size-fits-all approach, and there are other complicating factors stemming from the IRA. One thing we can sure of is that the balloon will not simply burst, the air (or, in this case, the dollars) will go somewhere. We can also be sure that CMS won’t be picking up the tab any time soon, and payers and drug manufacturers will have to control the squeeze.